The Grateful Dead’s January of ‘70 schedule was fairly packed with a dozen shows that began with two nights at the Fillmore East, and culminated in a booking to play the opening weekend of a brand-new New Orleans Tchoupitoulas Street club called A Warehouse. Fleetwood Mac served as the opening act, with the Chicago jazz rock band The Flock rounding out the bill.

The Dead and their roadies stayed at the Royal Sonesta Hotel, at 300 Bourbon Street in downtown New Orleans. The two dates fell in the thick of Carnival season so extracurricular shenanigans were surely in order. And so it followed that in the early hours of the evening after the Dead’s second weekend performance, the local fuzz paid a visit to the Royal Sonesta. Their surprise visit was most likely precipitated by the Jefferson Airplane’s bust for marijuana possession at the same hotel a few months earlier. Obviously, the New Orleans Police were actively suspicious of any out-of-town freaks. The next morning’s front-page story of the Times-Picayune was headlined “Drug Raid Nets 19 in French Quarter: Rock Musicians, ‘King of Acid’ Arrested.” Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, and Bill Kreutzmann were named in the paper as among those caught, in addition to then-manager John McIntire, and crew members Lawrence “Ramrod” Shurtliff and Donald “Rex” Jackson. Mickey Hart was also nabbed and booked under the moniker Summer Wind which originated from an ID he was carrying titled “Summer Wind: spiritual advisor to the Grateful Dead.” There’s always a Prankster in the bunch.

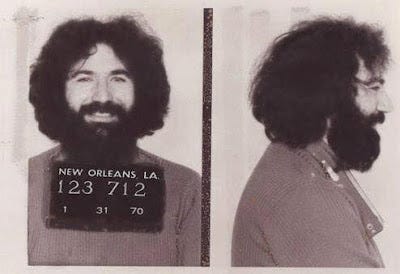

As for the bust, word is that the Federal Bureau of Narcotics had received three separate tips about the band a few days before the Warehouse shows. Two were credited to confidential informants and one to an anonymous letter that read in part: “The Dead have been boasting on the coast that they are going to turn New Orleans on because their friends, the Jefferson Airplane got busted here. I cannot tell you my name because they would hurt me. I used to date one of them.” The charges for band, crew, and friends included possession of LSD, barbiturates, marijuana, amphetamines, narcotics, and in Owsley’s case, “dangerous non-narcotics.” Garcia, who returned to the hotel a few hours after the rest of the band, was escorted to the police station and summarily booked. His mugshot is, of course, the stuff of legend.

Heralded as “Bread for the Dead,” the February 1st add-on show was essentially the Grateful Dead’s bust fund benefit for themselves. After they bailed out over a dozen people, the Dead were out of cash, a clear sign of the hand-to-mouth life of a touring band in those days. Fleetwood Mac's soundman Dinky Dawson detailed in his fine book Life On The Road (Billboard Books, 1998), that even though the New Orleans cops were out in force looking to bust pot smokers, buckets were passed around for people to drop money in to help the Dead, and in thanks the band passed around bottles of Cold Duck. They announced from the stage "it’s Electric Duck, so only take a few sips," and the New Orleans police, used to 200 years of vice, somehow missed the reference.

Our tape opens some wacky banter, after which the stage announcer says: “And here’s the group that made this afternoon all possible…” (Lesh: “The New Orleans Police Department!”). They launch into a torrid version of Beat It On Down the Line which, unfortunately, suffers from a terrible mix. China Cat Sunflower > I Know You Rider is next up; the sound remains guitar-heavy and messy, but levels out just before the customary three-part A cappella vocal harmony. A few new ones from the soon-to-be-released Workingman’s Dead follow—Black Peter and Cumberland Blues. Both songs are well played and sound remarkably tight despite the fact that they’d just been folded into the band’s repertoire. The middle portion of the show is pretty standard without any real standouts. Good Lovin’ cuts just as the jam is heading back into Pig’s vocals and Dire Wolf is still in its catchy folk tune phase.

They really dig in for back half of the performance. The Cryptical Suite is superb and typical of the era. The opening verse segues into an extremely long (11 minute) drum break, followed by a seething take on The Other One. A reel flip neatly cuts the vocals, resulting in a mostly instrumental version. The ensemble playing is absolutely fierce, and Garcia sounds like he’s about to blow up. Fleetwood Mac’s Peter Green joins the band on guitar as they drop into 39-minutes of Turn On Your Lovelight to close out the show. Green’s presence is felt immediately as he bends and blends notes on his ’59 Les Paul, deftly navigating the tempo changes that make the song such a delight. His contribution clearly inspires the band and the evening’s take is a very long, jammed out version that surely stands out as one of the most colorful Lovelights of the year.